Does the thought of finding an agent or publisher give you vapors? If so, you are in good company. Query letters are among the most important documents an author writes. Whether you are a full-time freelancer or a wannabe one-time writer hoping for publication of a memoir, your future hangs on that one page. It can make or break your chances of seeing your words between commercially printed covers.

Does the thought of finding an agent or publisher give you vapors? If so, you are in good company. Query letters are among the most important documents an author writes. Whether you are a full-time freelancer or a wannabe one-time writer hoping for publication of a memoir, your future hangs on that one page. It can make or break your chances of seeing your words between commercially printed covers.

Writing great query letters is a special art form, and not one that we learn in any classes in school. Some people complete their MFA in writing without learning this crucial skill. So what’s a person to do?

The traditional way to learn is to find a good book. You may find something in your library, but this is an important topic, and it’s worth having something on hand to refer to whenever you need it.

I must include a disclaimer here. Since I had any clue at all about how to write, I’ve only written one query letter and received an acceptance within half an hour of sending the email. That was to a local newspaper and I included the story cold, so it wasn’t a true query letter. Both my traditionally published books were pitched in a face-to-face meeting, without so much as a proposal. Remember the old saying, “It’s not what you know, it’s who you know”? That does help. Because I’m always as busy as I want to be without tracking down additional writing assignments, I don’t write query letters, so I can only offer suggestions.

What I suggest, besides scanning the titles on Amazon, is to surf over to visit Query Shark. That site has an amazing collection of query letters that have been critiqued by Janet Reid, an agent with the FinePrint Literary Management Agency.

Janet suggests that you read all the posts and learn from them. Now that there are more than 200, perhaps the most recent hundred will do. Then, if you wish, you may submit your query letter in hopes of having it anonymously critiqued. There are explicit instructions on how to accomplish this and increase the (slim) odds yours will be chosen. She focuses on fiction, but her Q&A page says she occasionally runs examples from other genres (like memoir).

A couple of paragraphs way down one page on the AgentQuery site advises you that memoirs are marketed like fiction, so Janet’s models should give you terrific guidance.

Miss Snark, the literary agent seconds AgentQuery’s advice that the memoir must be finished and polished before querying. She adds further that “You get one shot on this. Don't **** it up by querying before your ms is ready.” Check out other topics on her site. She retired after two years, but her helpful posts remain, and her blog writing format differs from QueryShark’s.

On her PubAgent blog, Agent Kristin advises that “Writing a memoir is not therapy.” Focus on the artistic merits of your work, not the fact that writing it changed your life. Art sells, therapy doesn’t.

Lynn Griffin has uplifting news in her “Easy-Peasy Query Letter” post on The Writers’ Group blog. “Writing a query letter for fiction or memoir should take no more than 15-20 minutes tops. Assuming, of course, you've been researching agents while writing your book.”

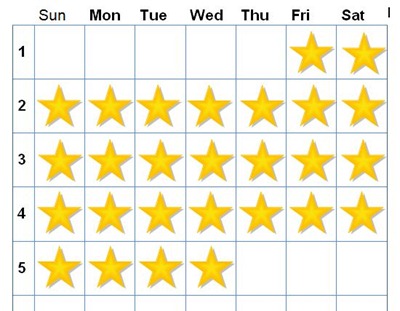

Research. Aw, yes. All agents want to read queries they way they ask for them to be written. Read and study their sites. Know what they handle, how they want to be approached, and anything else they tell you. Then write away. Your odds will be much higher if you study this subject before you start collecting those infamous rejection slips. Perhaps you’ll win the submissions lottery on your first submission.

Write now: read a couple of AgentQuery’s columns, then practice writing a query letter for your story or memoir. Who knows? You might find someone to send it to, now or later.